Why is it that for some breast cancer patients, a surgeon resects a tumor and they are cancer-free for 20+ years, whereas other patients have metastasis accelerate at an uncontrollable way after the tumor resection? This is a question that Katie Parkins, one of the trainees in Western University’s Cellular and Molecular Imaging program at Robarts Research Institute, strives to answer.

Why is it that for some breast cancer patients, a surgeon resects a tumor and they are cancer-free for 20+ years, whereas other patients have metastasis accelerate at an uncontrollable way after the tumor resection? This is a question that Katie Parkins, one of the trainees in Western University’s Cellular and Molecular Imaging program at Robarts Research Institute, strives to answer.

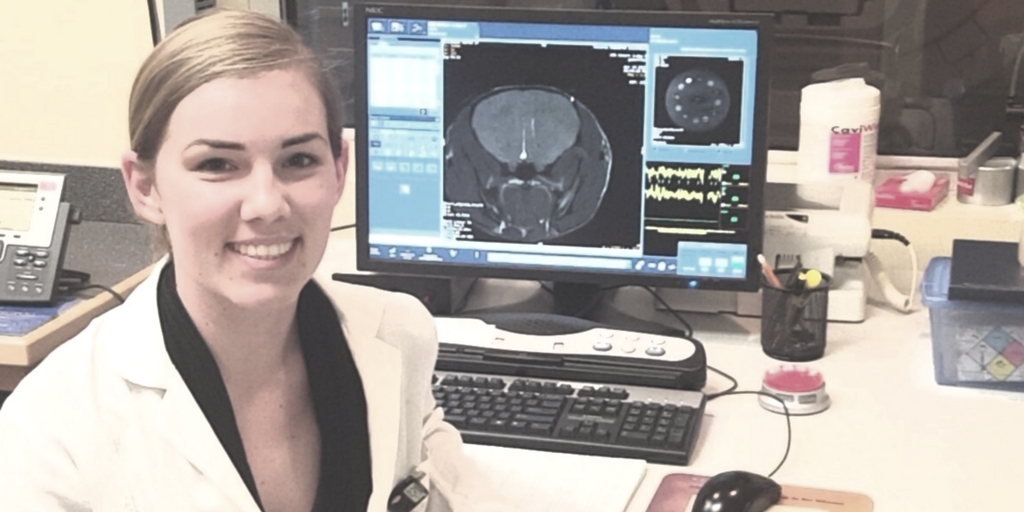

While doing her undergrad, Katie Parkins became interested in imaging the brain and understanding how to tie it back to cancer. “Some researchers are studying mechanisms of disease such as cancer, imaging and technology development, or molecular biology. I love that my work encompasses all of these. In this sense, Western University has a great research environment. Everyone is working together, which I find exciting. And there are also unique technologies that other universities – not only in Ontario but even in North America – do not have.”

Katie is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Medical Biophysics as well as the collaborative Molecular Imaging program at Western University. She works under the co-supervision of Drs. Paula Foster and John Ronald. Katie is using imaging to explore the mechanisms that control metastatic growth rates. Specifically, the role of the primary tumour as both preclinical and clinical evidence suggests it can both suppress the growth of secondary tumours, a mechanism known as concomitant tumour resistance (CTR); as well as stimulate the growth of secondary tumours coined concomitant tumour enhancement (CTE).

Strikingly, some breast cancer patients are afraid to undergo surgery (or even a tumor biopsy!) because of a common belief: “Surgery could disrupt the tumour and spread the cells to other parts of the body.”

“This is not superstition,” Katie confirms. “There is clinical evidence of CTR when surgical removal of tumours resulted in a rapid metastatic growth. However, there is contrary evidence that the presence of a primary tumour can accelerate the metastatic outgrowth. Obviously, in the clinical setting, it is hard to study both mechanisms. I can’t imagine a surgeon who would say to the patient, ‘Well, let’s leave the cancer tumor inside your body and see what happens.’

“As a result, we have to try to make sense of some of the differences seen between two different groups of breast cancer patients: those who have their tumour resected and those who are seen as at less risk of spread and thus put on active surveillance. Under these conditions, the study I am currently involved with appears to be highly important.”

Basically, Katie and her research team facilitate brain metastasis in the lab animals and explore over time what is going on using advanced imaging technologies. “Regrettably, a lot of breast cancer patients are dying from brain metastasis, which can occur many years after successful removal of the primary tumour and adjuvant therapy. The goal of my work is to create a non-invasive imaging technique that will help understand the nature of that metastatic growth.”

Basically, Katie and her research team facilitate brain metastasis in the lab animals and explore over time what is going on using advanced imaging technologies. “Regrettably, a lot of breast cancer patients are dying from brain metastasis, which can occur many years after successful removal of the primary tumour and adjuvant therapy. The goal of my work is to create a non-invasive imaging technique that will help understand the nature of that metastatic growth.”

As mentioned earlier, the two imaging technologies that Katie currently employs are Cellular MRI and Bioluminescence Imaging (BLI). The first visualizes iron-labeled cells in a living organism such as lab mice. Cellular MRI allows Katie to track cells at the single cell level. However, it cannot differentiate between dead and viable cells. BLI, on the other hand, measures cellular viability. When combined, Cellular MRI and BLI provide a more comprehensive understanding of metastatic breast cancer cell fate.

“Combining these tools gives us information we have never had before,” Katie says enthusiastically. “In regular MRI images, you can see just a big tumor in the brain that is made up of many different cells. In our study, we take the gene from the firefly and then engineer cancer cells that express this gene. In simple terms, we make our cancer cells glow like the firefly. The main advantage of using BLI is that we get signals only from live cancer cells. This is an advantage when studying treatment models where in the case of an effective drug, the signal will decrease due to cells dying off.”

The next step Katie undertakes in her research is to explore animals with a primary tumor and those without a primary tumor. “Information that we are getting by using the advanced imaging technologies in animals would be very translational. Currently, my primary research objective is to understand the mechanisms by which the primary tumour controls the growth of secondary tumours. Ultimately, this may lead to novel therapies for metastatic breast cancer patients.”

Katie recently presented her work at the Canadian Cancer Research Conference in Vancouver. “I not only had the opportunity to discuss my latest findings with other cancer researchers but also metastatic breast cancer patients that are part of the Canadian Patient Involvement program. Seeing the patients’ interest in my work is very encouraging. It gives me inspiration and passion to go further and overcome challenges every researcher faces in their work.”

Katie recently presented her work at the Canadian Cancer Research Conference in Vancouver. “I not only had the opportunity to discuss my latest findings with other cancer researchers but also metastatic breast cancer patients that are part of the Canadian Patient Involvement program. Seeing the patients’ interest in my work is very encouraging. It gives me inspiration and passion to go further and overcome challenges every researcher faces in their work.”

Support researchers like Katie Parkins and others by considering a donation to the Breast Cancer Society of Canada. Find out how you can help fund life-saving research, visit bcsc.ca/donate

Katie Parkins’s story was transcribed from interviews conducted by BCSC volunteer Natalia Mukhina – Health journalist, reporter and cancer research advocate

Natalia Mukhina, MA in Health Studies, is a health journalist, reporter and cancer research advocate with a special focus on breast cancer. She is blogging on the up-to-date diagnostic and treatment opportunities, pharmaceutical developments, clinical trials, research methods, and medical advancements in breast cancer. Natalia participated in numerous breast cancer conferences including 18th Patient Advocate Program at 38th San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. She is a member of The Association of Health Care Journalists.

Natalia Mukhina, MA in Health Studies, is a health journalist, reporter and cancer research advocate with a special focus on breast cancer. She is blogging on the up-to-date diagnostic and treatment opportunities, pharmaceutical developments, clinical trials, research methods, and medical advancements in breast cancer. Natalia participated in numerous breast cancer conferences including 18th Patient Advocate Program at 38th San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. She is a member of The Association of Health Care Journalists.