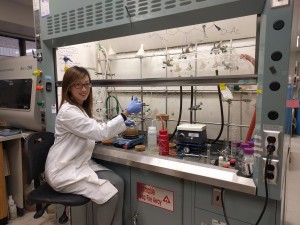

Alexandra Hauser-Kawaguchi, a PhD candidate in Dr. Len Luyt’s lab at the London Health Science Centre’s London Regional Cancer Program, works to help breast cancer patients fight the disease, but does so from her chemistry lab.

Alexandra Hauser-Kawaguchi, a PhD candidate in Dr. Len Luyt’s lab at the London Health Science Centre’s London Regional Cancer Program, works to help breast cancer patients fight the disease, but does so from her chemistry lab.

“The drug development process that we focus on in our lab is on basic science. We carry out the first steps in the discovery of new anti-cancer drugs. As a chemist, I synthesize novel compounds, and then, I work with biologists, who screen them in cells. If it looks successful, we move onto animal models. But quite often, the outcome leads me to having to redesign and redeveloping the compounds. This is how a successful drug molecule is discovered.”

What Alexandra studies specifically has a long and complicated name – Receptor for hyaluronan mediated motility (RHAMM). “Basically, any receptor is a protein molecule that can react to chemical signals from outside the cell. When such signals arrive, and bind to the receptor, it responds in a certain way. RHAMM reacts specifically to hyaluronan (HA) signals. In breast cancer cells, their interaction increases.”

What follows is a domino effect. “The RHAMM-HA interaction activates downstream signaling pathways. Breast cancer cells, especially those of an aggressive nature, begin to rapidly exchange signals. This process, in turn, activates genes responsible for spreading the cancer to other body parts, which means that it unfortunately becomes metastatic, and this often means that it is ‘incurable’. Yet, the good news is that we can prevent this scenario if we don’t let RHAMM and HA interact.”

For a few years, Alexandra has been focused on discovering new therapeutic agents – drugs – that could block the interaction between RHAMM and HA. “We have developed peptides that act as RHAMM mimics. Proteins and peptides are very similar in structure, but peptides are smaller. RHAMM mimics bind strongly with HA and prevent it from interacting with the real RHAMM. Our studies show that these peptides can block inflammation associated with breast cancer, as well as stop metastasis from occurring.”

Recently, Alexandra’s team has created a set of such peptides and conducted preclinical evaluation in mice. “Preliminary results demonstrated that our lead compound may be successful, and it will be further investigated as a prototype drug molecule for treating RHAMM-related breast cancer.”

“In a perfect world, we hope to one day test our therapeutic agent in patients. Unfortunately, it takes years and requires funding to reach that point. Even preclinical studies are quite expensive. In our lab, we have to be very rigorous with everything leading up to the preclinical stage before we are confident enough to move forward to a clinical trial.”

Going further in describing the process of drug development, Alexandra suggests that the prospective drug would be injectable, like a vaccine. In addition, the team is thinking of the possibility for the drug to be taken orally: “We are working on designing our compounds in such a way that one day it could end up being a pill. No blood, no needles – it would be much more convenient for patients.”

Going further in describing the process of drug development, Alexandra suggests that the prospective drug would be injectable, like a vaccine. In addition, the team is thinking of the possibility for the drug to be taken orally: “We are working on designing our compounds in such a way that one day it could end up being a pill. No blood, no needles – it would be much more convenient for patients.”

In Alexandra’s opinion, the most exciting part of research is that it is all about discovering things. However, there is also a negative side. “Quite often experiments fail. You spend so long trying to solve a problem, but it often doesn’t work out like you expected. Such moments can be a bit heartbreaking and discouraging. But when something does work, it is extremely rewarding, and it reminds me why I do this.”

After graduating from University of Toronto, she chose Western University in London for her doctorate because of its reputation in health research, imaging and radiopharmaceuticals. Alexandra was actually first involved in the development of imaging agents. This is directly related to PET (positron emission tomography) or SPECT (single-photon emission computerized tomography) scan technologies. These nuclear imaging tests use very small doses of radioactive compounds that are injected into patients, which helps visualize the cancer tumor on the scan.

“Starting with work in imaging/diagnostics, I ended up working on drug molecules for therapeutic applications in cancer. I do not believe in a magical cure for everything. Each type of cancer is very different, and each patient is very different. But I definitely think it is possible to develop drugs that will treat specific types of breast cancers in the future.”

Support researchers like Alexandra Hauser-Kawaguchi and others by considering a donation to the Breast Cancer Society of Canada. Find out how you can help fund life-saving research, visit bcsc.ca/donate

Alexandra Hauser-Kawaguchi’s story was transcribed from interviews conducted by BCSC volunteer Natalia Mukhina – Health journalist, reporter and cancer research advocate

Natalia Mukhina, MA in Health Studies, is a health journalist, reporter and cancer research advocate with a special focus on breast cancer. She is blogging on the up-to-date diagnostic and treatment opportunities, pharmaceutical developments, clinical trials, research methods, and medical advancements in breast cancer. Natalia participated in numerous breast cancer conferences including 18th Patient Advocate Program at 38th San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Natalia Mukhina, MA in Health Studies, is a health journalist, reporter and cancer research advocate with a special focus on breast cancer. She is blogging on the up-to-date diagnostic and treatment opportunities, pharmaceutical developments, clinical trials, research methods, and medical advancements in breast cancer. Natalia participated in numerous breast cancer conferences including 18th Patient Advocate Program at 38th San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

She is a member of The Association of Health Care Journalists.